Worldbuilder

The hardest part of writing fantasy isn’t the writing part — it’s the worldbuilding. From scratch, we have to create not only characters and plot but also an entire world, sometimes entire universes! Ask any genre writer and they’ll be able to tell you why God rested on the seventh day, trust me.

Often, I’ve thought of myself more as a worldbuilder than a writer. As much as I love telling a story — and telling it well — my favorite part of the entire process is the pre-pre-writing, the time when I draw maps and create cultures and design languages. It’s the potter kneading the clay, the painter mixing his colors, the fashion designer choosing his fabrics. If you don’t have a proper world in which to couch your characters and your story, even the best protagonist and plot will fall short.

Here, you can read about a few of the worlds I’ve created — how they started, what goals I had in mind as I built them, what I like most about them. I hope they’ll captivate you as much as they did me!

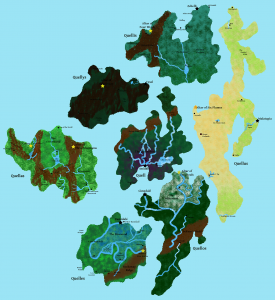

The Great Island Nation of the Coquels

The Coquels is an archipelago literally infused with elemental magic, so strange things happen on the islands — water flows backwards sometimes, for instance, and fire doesn’t always burn. The magic, known as quell, is a sentient force, though very few of the inhabitants know that, and it infuses all the lands of Palia, not just the Coquels. The western lands of Spalor, for instance, have a subtle magic that allows them to commune better with animals, and the eastern Calerelacians have a shamanic calling that gives them power over natural forces like lightning and storms. To the north, the barren deserts of the Offlands are home to twisters, fierce warriors who bind with quell to become avatars of the elements.

Elemental magic is not particularly unique to fantasy fiction, but the Coquels is, I hope, unlike any other place you’ve seen. My intent with the Coquellians was to create a civilization very similar to ours with regard to quality of life and creature comforts, only one that uses magic instead of technology to achieve these ends. Consequently, the Coquellians have household appliances that you’d recognize; they speak just like you and I do, so the twenty-something characters in my first published novel, Eternity in an Hour, say things like, “Dude, what’s up?” and “Let’s hang out.” Perhaps not surprisingly, this is a love-it-or-hate-it change to the trope, but I’m okay with that.

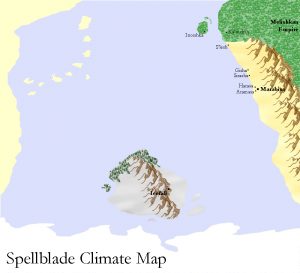

Icefall

Icefall came out of my attempt to write a traditional high fantasy story in a traditional, geographically sound (perhaps this makes it non-traditional after all?) high fantasy setting. I had just finished reading a few textbooks on physical geography, and I really wanted to try to build an entire world based on scientific principles, things like ocean currents and jet streams and tectonic activity. It was a long, arduous process, but one I enjoyed, despite the numerous cartographic (mis)steps along the way.

The story here, The Other’s Mine, again follows a traditional high fantasy epic plot, albeit one with two gay guys as the primary focus. Trevin is a Spellblade, a powerful battle-mage who weaves magic into his attacks. After the Crown Prince of Icefall kidnaps their queen, the Marabisan Protectorate declares war on the frozen island nation. Trevin must lead his Spellblades against the Wild Fleet, Icefall’s undefeated military force, and their ddraig, dragon-like beasts with heightened emotional connections to the warriors who ride them. When Icefall captures Trevin, however, he realizes that the noble war he’s fighting may not be as noble as he thinks.

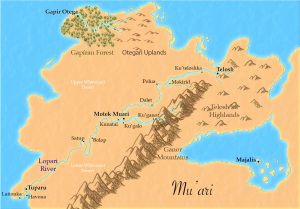

Mu’ari

Mu’ari is another world that developed out of an idea for a story: here, the planet is ringed, and some of the native cultures, such as the Motek, view those rings as the remnants of gods who sacrificed their earthly lives to keep Chaos at bay. From the planet’s surface, the rings don’t look like rings: they’d look like striations in the sky, and this banded appearance has led to a culture that is highly stratified, from slaves through nobles to royalty, and nearly draconian in its adherence to rules and regulations.

I have only one novel planned for Mu’ari: Fourteen Lines, after the late Edna St. Vincent Millay sonnet, “I will put Chaos into fourteen lines.” At the start of the novel, the rings disappear; although I think this is an astronomical impossibility, it’s great for conflict! As the Motek civilization derails, five people — a king, a priest, an artisan, and two slaves — have to grapple with slavery and freedom and what, ultimately, these ideas really mean.